Featured image credit: Rocket Lab

Lift Off Time | May 15, 2021 – 11:11 UTC | 23:11 NZST |

|---|---|

Mission Name | Running Out of Toes, two Earth observation microsatellites for BlackSky’s constellation |

Launch Provider | Rocket Lab |

Customer | Spaceflight Inc. for BlackSky |

Rocket | Electron |

Launch Location | Launch Complex-1A, Māhia Peninsula, New Zealand |

Payload mass | 120 kg (~260 Ibs) |

Where did the satellites go? | They were supposed to go into 430 km circular low Earth orbit (LEO) at 50° inclination |

Did they attempt to recover the first stage? | Yes, it was their second attempt |

Where did the first stage land? | It softly landed in the ocean ~650 km downrange from the launch pad |

Did they attempt to recover the fairings? | No, this is not a capability of Electron |

Were these fairings new? | Yes |

How was the weather? | Upper-level winds caused a hold at T-00:02:13 and delayed the launch |

This was the: | – 20th Electron launch – 3rd Rocket Lab launch of 2021 – 2nd planned ocean splashdown recovery mission – 42nd orbital launch attempt of 2021 – 3rd unsuccessful mission in Rocket Lab’s history |

Where to watch | Official replay Everyday Astronaut replay |

How did it go?

Not very well! Running Out of Toes’ mission was quite different from the previous two this year. On this mission, Electron was supposed to deliver two Earth-observation microsatellites for BlackSky’s constellation into a 430 km low Earth orbit (LEO), at 50° inclination. Unfortunately, Running Out of Toes did not go as planned.

Lost Payload

Rocket Lab launched Running Out of Toes from Launch Complex-1A (LC-1), Māhia Peninsula, New Zealand. Electron successfully lifted off the launch pad and proceeded through a nominal Stage 1 engine burn, Stage 1 separation, and Stage 2 ignition. However, almost immediately after that, an issue was reported by an engine computer, which resulted in the upper stage shutting down. Subsequently, this launch did not make it into orbit and the mission was lost. Rocket Lab reported that this behavior had not been observed previously during various ground testing operations.

Successful Recovery Mission

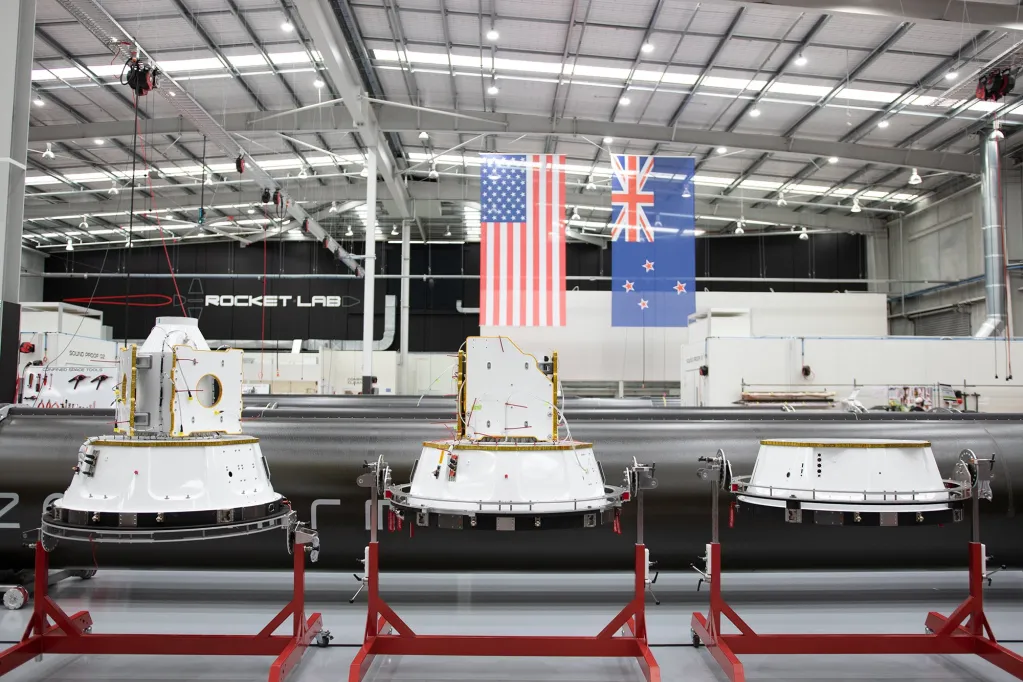

Moreover, this launch was Rocket Lab’s second attempt to safely return Electron’s first stage to Earth from space. Despite the anomaly with the upper stage, Rocket Lab was able to proceed with recovery steps. The first stage safely landed in the ocean under the parachute, and Rocket Lab’s recovery team retrieved it from the water and returned it to the production complex.

After inspection of the booster, the company mentioned that the engines were in good condition and will be further analyzed in engine hot fire tests. This recovery mission was also a debut flight for a redesigned stainless steel heat shield on the first stage. According to the company, it seemed to perform well and protected Stage 1 from the enormous heat loads and forces during re-entry.

Mission

Payload

Running Out of Toes was supposed to be a dedicated mission to lift two 60 kg microsatellites for BlackSky’s global constellation. This was not the first time that Rocket Lab provided launch services for BlackSky. Three of their Earth-observation satellites had already been successfully deployed by Electron across 2019 and earlier this year on the rideshare mission They Go Up So Fast. Seattle-based Spaceflight Inc. was responsible for arranging the launch, as well as for the mission management and integration services for BlackSky.

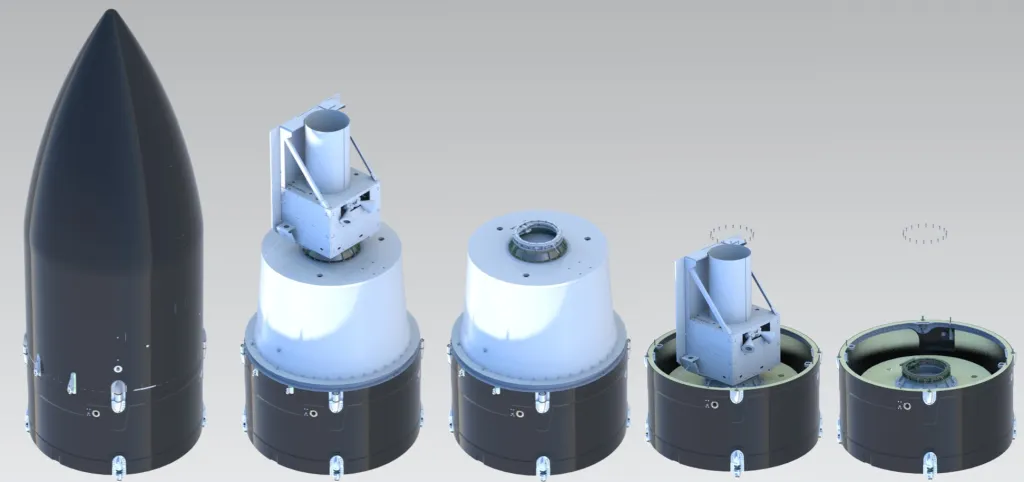

For this mission, Rocket Lab used an interesting Russian doll-like payload’s configuration in the fairing. More particularly, BlackSky’s two microsatellites were double stacked on top of each other using another payload adapter for deployment from Electron’s Kick Stage.

Once in orbit, BlackSky’s two Gen-2 satellites can capture images of Earth with submeter resolution. The company uses artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to handle this universe of data in the most efficient way. Using AI/ML algorithms, BlackSky’s analytics platform can track the world’s news for emerging events and task microsatellites to image them, which provides time-sensitive and critical information to early responders.

Because of the experienced issue with the upper stage, Electron did not reach the dedicated orbit and did not deploy BlackSky’s payload. BlackSky’s two microsatellites were, therefore, lost.

Second Recovery Attempt

For this launch, Rocket Lab had another important goal: recovering the first stage after its short sub-orbital trip to space. This mission was the second attempt in the history of the company to safely bring the launch vehicle back home. Rocket Lab first attempted a soft splashdown last November. As a result, Return to Sender’s mission provided crucial data on the actual stresses that Electron’s booster was experiencing during re-entry.

With this information in hand, Rocket Lab upgraded the vehicle with a beefed-up heat shield to protect it from enormous heat pressure during its descent. It is achieved by directing the force of plasma away from the first stage. The improved stainless steel heat shield can deal with thermal loads much more efficiently, as compared to the previous version made of aluminum.

Rocket Lab’s Recovery Program

The company has revealed its plans for the recovery program in 2019. The global aim of this program is to safely recover and re-fly Electron’s first stage. This would allow the company to increase launch cadence even further by reducing production time spent to build new first stages from scratch.

Rocket Lab’s recovery program is divided into two phases. The first one consists of three ocean splashdown recovery missions, where a full Electron first stage is recovered from the water and shipped back to the production complex for closer inspection. On these flights, Rocket Lab will gather the necessary data needed for understanding the recovery process and introducing updates to the vehicle’s design. Then, the company intends to move into the second phase of the recovery program – mid-air recovery with a helicopter.

In his latest interview with Everyday Astronaut, Rocket Lab’s Founder and Chief Executive Peter Beck mentioned that Running Out of Toes’ mission would use some of the booster’s components that had already flown on the previous recovery launch Return to Sender. More particularly, its propellant pressurization system traveled to space and back for the second time.

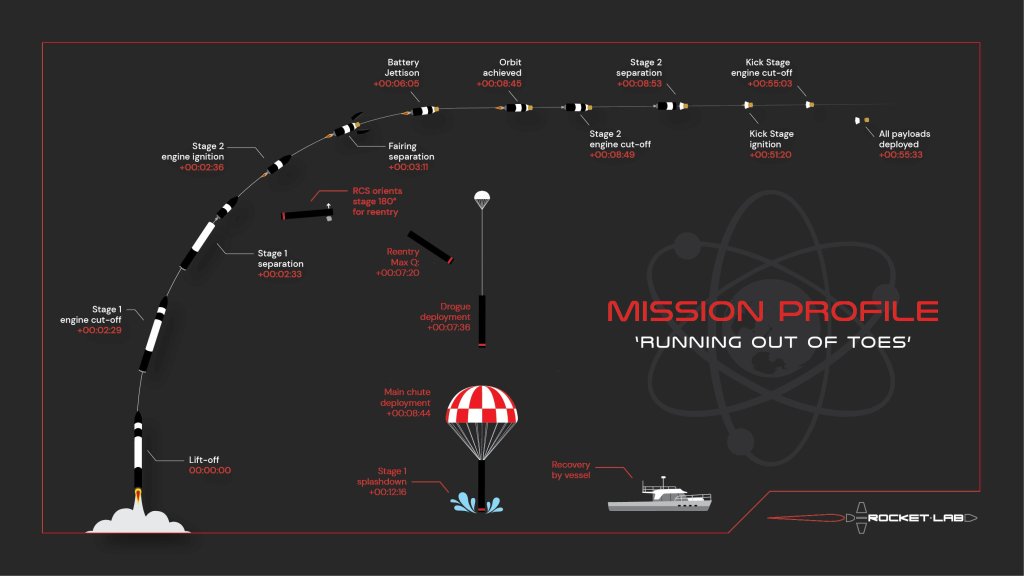

Recovery Mission Profile

Fortunately, the anomaly with the upper stage did not have an impact on the recovery of Electron’s first stage. This mission’s retrieval process went as follows. After successful Stage 1 separation, the reaction control system reoriented the booster 180° for re-entry. This orientation, as well as the heat shield, helped the vehicle withstand temperatures up to 2400°C as it was re-entering Earth’s atmosphere at hypersonic speeds (~8 times the speed of sound). After decelerating to supersonic speeds (< Mach 2), Electron deployed a drogue parachute that stabilized the stage and continued slowing it down. Then, the main parachute came into play to increase drag even further and make a soft landing in the ocean possible. There, Rocket Lab’s recovery crew fished Electron out of the water using a new retrieval method: the Ocean Recovery Capture Apparatus (ORCA). The recovered stage was then returned to the production complex for inspection.

Therefore, Running Out of Toes’ mission provided Rocket Lab with even more data on the recovery process and efficiency of the introduced updates. This information will help to make necessary adjustments and get prepared for the third and final ocean splashdown recovery mission that is scheduled before the end of this year. The final mission will see another update in the vehicle’s design that includes an additional deployable decelerator to deal with thermal loads in a much more aggressive way. If everything goes as planned, Rocket Lab will be able to move into the final phase of the recovery program – mid-air recovery with a helicopter. Check out their demo video that illustrates all steps of the recovery program!

Timeline

Pre-Launch

| Hrs:Min:Sec From Lift-Off | Events |

| – 04:00:00 | Road to the launch site is closed |

| – 04:00:00 | Electron is raised vertical, fueling begins |

| – 02:30:00 | Launch pad is cleared |

| – 02:00:00 | LOx load begins |

| – 02:00:00 | Safety zones are activated for designated marine space |

| – 00:30:00 | Safety zones are activated for designated airspace |

| – 00:12:00 | GO/NO GO poll |

| – 00:02:13 | Because of the strong upper-level winds, the launch was on hold for about 46 min |

| – 00:18:00 | New countdown started |

| – 00:12:00 | GO/NO GO poll after the hold |

| – 00:02:00 | Launch auto sequence begins |

Launch

| Hrs:Min:Sec From Lift-Off | Events (Recovery Events Are In Orange, |

| – 00:00:02 | Rutherford engine ignition |

| 00:00:00 | Lift-Off |

| + 00:02:30 | Main Engine Cut Off (MECO) on Electron’s first stage |

| + 00:02:33 | Stage 1 separation |

| + 00:02:36 | Stage 2 Rutherford engine ignition |

| + 00:03:11 | |

| + 00:06:05 | |

| + 00:07:20 | Stage 1 re-entry Max Q |

| + 00:07:29 | Stage 1 drogue parachute deployment |

| + 00:07:50 | Stage 1 is subsonic |

| + 00:08:40 | Stage 1 main parachute deployment |

| + 00:08:44 | Stage 1 ocean splashdown |

| + 00:08:45 | |

| + 00:08:53 | |

| + 00:51:20 | |

| + 00:53:03 | |

| ~+ 01:00:00 |

At T+00:01:20 and 15 km altitude, Electron has successfully passed through Max Q with propulsion continuing nominally. A minute later, 9 Rutherford engines on Electron’s first stage throttled down followed by successful Stage 1 separation and Stage 2 ignition. This is when the issue with the upper stage’s engine occurred. As a result, the engine computer commanded a safe shutdown of Electron’s upper stage. Fortunately, it remained within the predicted launch corridor and did not cause any harm to the public, the LC-1 launch site, or Rocket Lab’s launch or recovery crews.

What Is Electron?

Rocket Lab’s Electron is a small-lift launch vehicle designed and developed specifically to place small satellites (CubeSats, nano-, micro-, and minisatellites) into low Earth orbits (LEO) and Sun-synchronous orbits (SSO). Electron consists of two stages with optional third stages.

Electron is about 18 meters (59 feet) in height and only 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) in diameter. It is not only small in size, but also light-weighted. The vehicle structures are made of advanced carbon fiber composites, which yields an enhanced performance of the rocket. Electron’s payload lift capacity to LEO is 300 kg (~660 lbs).

The maiden flight It’s A Test was launched on May 25, 2017, from Rocket Lab’s Launch Complex-1 (LC-1) in New Zealand. On this mission, a failure in the ground communication system occurred, which resulted in the loss of telemetry. Even though the company had to manually terminate the flight, there was no larger issue with the vehicle itself. Since then, Electron has flown a total of 19 times (17 of them were fully successful) and delivered 104 satellites into orbit.

First and Second Stage

| First Stage | Second Stage | |

|---|---|---|

| Engine | 9 Rutherford engines | 1 vacuum optimized Rutherford engine |

| Thrust Per Engine | 24 kN (5,600 Ibf) | 25.8 kN (5,800 Ibf) |

| Specific Impulse (ISP) | 311 s | 343 s |

Electron’s first stage is composed of linerless common bulkhead tanks for propellant, and an interstage, and powered by 9 sea-level Rutherford engines. The second stage also consists of tanks for propellant (~2,000 kg of propellant) and is powered by a single vacuum optimized Rutherford engine. The main difference between these two variations of the Rutherford engine is that the latter has an expanded nozzle that results in improved performance in near-vacuum conditions.

Rutherford Engine

Rutherford engines are the main propulsion source for Electron and were designed in-house, specifically for this vehicle. They are running on rocket-grade kerosene (RP-1) and liquid oxygen (LOx). There are at least two things about the Rutherford engine that make it stand out.

Firstly, all primary components of Rutherford engines are 3D printed. Main propellant valves, injector pumps, and engine chamber are all produced by electron beam melting (EBM), which is one of the variations of 3D printing. This manufacturing method is cost-effective and time-efficient, as it allows to fabricate a full engine in only 24 hours.

Moreover, Rutherford is the first RP-1/LOx engine that uses electric motors and high-performance lithium polymer batteries to power its propellant pumps. These pumps are crucial components of the engine as they feed the propellants into the combustion chamber, where they ignite and produce thrust. However, the process of transporting liquid fuel and oxidizer into the chamber is not trivial. In a typical gas generator cycle engine, it requires additional fuel and complex turbomachinery just to drive those pumps. Rocket Lab decided to use battery technology instead, which allowed eliminating a lot of extra hardware without compromising the performance.

Running Out of Toes will bring another important highlight in the company’s history by launching the 200th Rutherford engine into space!

Different Third Stages

Kick Stage

In addition, Electron has optional third stages, also known as the Kick Stage, Photon, and deep-space version of Photon. The Kick Stage is powered by a single Curie engine that can produce 120 N of thrust. Like Rutherford, it was designed in-house and is fabricated by 3D printing. Apart from the engine, the Kick Stage consists of carbon composite tanks for propellant storage and 6 reaction control thrusters.

Basically, the Kick Stage in its standard configuration serves as in-space propulsion to deploy Rocket Lab’s customers’ payloads to their designated orbits. It has re-light capability, which means that the engine can re-ignite several times to send multiple payloads into different individual orbits. A recent example includes Electron 19th mission, They Go Up So Fast, launched in March earlier this year. The Curie engine was ignited to circularize the orbit, before deploying a payload to 550 km. Curie then re-lighted to lower the altitude to 450 km, and the remaining payloads were successfully deployed.

Photon and deep-space Photon

Moreover, Rocket Lab offers an advanced configuration of the Kick Stage, its Photon satellite bus. Photon can accommodate various payloads and function as a separate operational spacecraft supporting long-term missions. Among the features that it can provide to satellites are power, avionics, propulsion, and communications.

But there is more to it. In addition, Photon also comes as a deep-space version that will carry interplanetary missions. It is powered by a HyperCurie engine, an evolution of the Curie engine. The HyperCurie engine is electric pump-fed, so it can use solar cells to charge up the batteries in between burns. It has an extended nozzle to be more efficient than the standard Curie, and runs on some “green hypergolic fuel” that Rocket Lab has not yet disclosed. NASA already plans to use the deep-space version of Photon for its robotic Moon mission CAPSTONE. On this mission, the Photon spacecraft will deliver NASA’s 25 kg CubeSat into a unique lunar orbit, formally known as a near rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO). You can read more about CAPSTONE here.